Table of Contents

- The most important heuristics (in plain English)

- High-level flow inside Readability.parse()

- Core idea: score blocks, then pick a container

- How Readability.js thinks about “main content”

- Post-processing: fixing URLs and simplifying the output

- Why the algorithm fails (and what it usually means)

- Final output: what Readability.parse() returns

- WebCrawlerAPI main_content_only (real life shortcut)

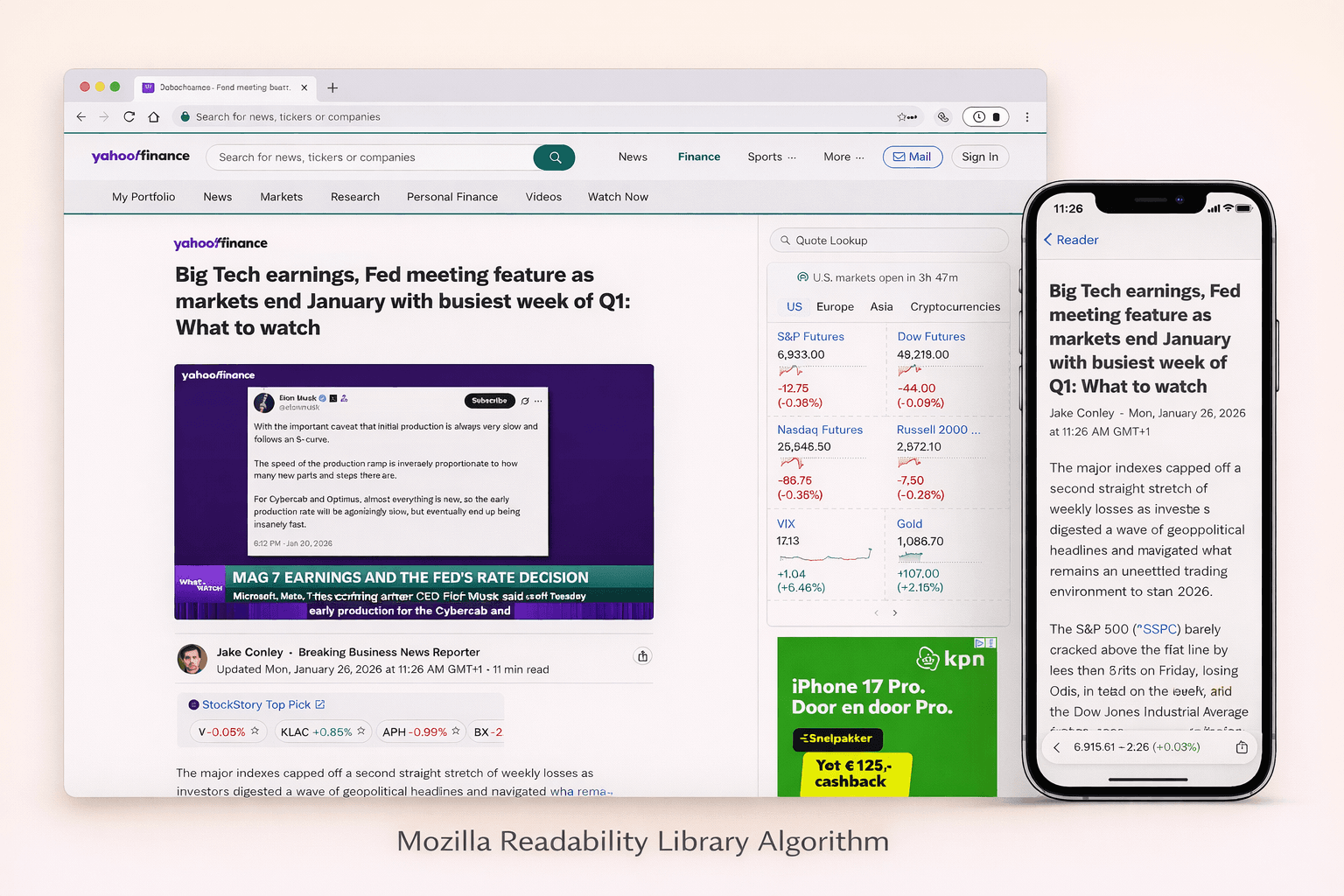

Hi, I’m Andrew. I’m a software engineer and a scraping browser expert. I have been using the Mozilla Readability library in WebcrawlerAPI for a long time now. In this post, I will share how the algorithm actually works. Readability.js looks simple from the outside: give it HTML, get back an article. Inside it is a bunch of small heuristics that try to survive real websites.

The most important heuristics (in plain English)

This is what makes the algorithm work most of the time:

- “Unlikely candidates” removal. Sidebars, ads, and share widgets often have obvious class/id names.

- Class/id weighting. Positive names get bonus. Negative names get penalty.

- Link density. Link-heavy blocks are usually navigation, not content.

- Text length and punctuation. Longer text with commas looks like real writing.

- Parent score propagation. Articles live inside containers.

- Sibling merging. Many sites split articles into multiple blocks.

- Conditional cleanup. Remove stuff like forms, embeds, and weird lists, but only when it looks like junk.

High-level flow inside Readability.parse()

Readability.parse() is a pipeline. It does a few passes over the DOM, and each pass has one job.

High level steps:

- Preprocess the document (remove obvious noise and normalize the DOM).

- Extract metadata (title, byline, excerpt, site name, publish time).

- Find the article container with _grabArticle() (this is the core algorithm).

- Clean the chosen container with _prepArticle() (remove junk, fix images, simplify).

- Post-process output (fix URLs, remove nested wrappers, strip classes if needed).

- Return the final article object (HTML + text + metadata).

Real life note: it can retry step 3-4 with less aggressive cleanup if the result is too short. This is why it works on many weird pages, but it is also why it is not “free” CPU-wise.

Core idea: score blocks, then pick a container

Readability works like this:

- Find many small blocks (mostly p, pre, td, headings, and some div after normalization).

- Give each block a score based on how “article-like” its text is.

- Add that score to parent containers.

- Pick the best container (the “top candidate”).

This is important. In real life, the article is not a single paragraph. It is usually a div or article that contains many paragraphs. So Readability scores the leaf blocks, but the winner is often a parent node.

The scoring rules are simple (and very practical):

- Very short text is ignored.

- More commas usually means more sentences (good signal).

- Longer text gets a small bonus, but it is capped.

- Link-heavy blocks get punished.

Here is a small scoring example, close to what Readability does:

// Node 18+

export function scoreText(text) {

const t = (text || "").trim();

if (t.length < 25) return 0;

let score = 1;

score += (t.match(/,/g) || []).length;

score += Math.min(3, Math.floor(t.length / 100));

return score;

}

Then Readability pushes that score up the tree. Parent gets more, grandparents get less. This is how it finds the container that “owns” most of the real text.

How Readability.js thinks about “main content”

When people say “main content”, they usually mean: the part you would copy-paste into a note. Not the header. Not the menu. Not “related posts”. Just the article.

Readability.js does not use one magic selector. In real life every website is different, so it uses a few simple signals together:

- Text blocks with real sentences get points.

- Blocks with too many links lose points (navigation is mostly links).

- Scores are pushed to parent containers (because the real article is usually a wrapper).

- It removes “unlikely” blocks early, but it can retry with softer rules if it gets a short result.

The key tradeoff is simple: if cleanup is too aggressive, you lose real text. If cleanup is too soft, you keep junk.

Here is a tiny example of one important signal: link density.

// Node 18+

// Rough idea: menus have high link density, articles usually don't.

export function linkDensity(el) {

const text = (el.textContent || "").trim();

if (!text) return 0;

let linkTextLen = 0;

for (const a of el.querySelectorAll("a")) {

linkTextLen += (a.textContent || "").trim().length;

}

return linkTextLen / text.length;

}

Preflight: isProbablyReaderable (fast check before full parse)

Before running the full algorithm, Readability has a quick check: isProbablyReaderable(). It answers one boring but important question: “Is this page even worth parsing?”

In real life you crawl a lot of pages that are not articles:

- home pages

- category pages

- search pages

- login pages

Full parsing is heavier (DOM walk + scoring + cleanup), so this preflight tries to save time. It looks for a few candidate nodes (p, pre, article, and some div patterns), ignores hidden/unlikely blocks, and adds up a score based on text length. If the total score is high enough, the page is "probably readerable".

Post-processing: fixing URLs and simplifying the output

After Readability finds the article, it still does some cleanup to make the output stable. This part is easy to miss, but it matters in real life.

What it does:

- Converts relative URLs to absolute URLs (links, images, video/audio sources, srcset).

- Removes javascript: links (or turns them into plain text).

- Removes pointless nested wrappers (div inside div inside div) when it can.

- Strips class attributes unless you want to keep them.

- Detects text direction (dir) and keeps language (lang) when it is available.

Why it matters:

- If you save extracted HTML and render it later, relative URLs will break.

- If you feed extracted HTML into a markdown converter, deep wrappers make output noisy.

- If you keep classes from random websites, your CSS can get weird.

Why the algorithm fails (and what it usually means)

Readability fails when the page does not look like an article. Or when the “article” is there, but it is hidden behind layout tricks.

Common reasons:

- Not enough text. The page is a list, or a short announcement.

- Too many links. Navigation blocks can win if the page is mostly links.

- Content is split into many small blocks with little text.

- The DOM is broken (bad nesting) and the algorithm scores the wrong container.

- Heavy templates: the same “chrome” (header/sidebar/footer) has more text than the real article.

Real life caveat: Readability works on the HTML you give it. If you fetch a JS app and you get an empty shell, the algorithm has nothing to score.

Final output: what Readability.parse() returns

The result is a plain object. The important fields are:

- title

- byline

- excerpt

- siteName

- publishedTime

- content (clean HTML)

- textContent (plain text)

- length (characters)

- lang

- dir

In practice, I treat textContent + title as the “real payload”, and everything else as optional metadata.

WebCrawlerAPI main_content_only (real life shortcut)

If you just need the result and you don’t want to maintain your own extraction stack, WebCrawlerAPI has main_content_only. It runs the same kind of “find main content” logic for you and returns only the article.

If you want to test it fast, use this tool: Readability tool.

const response = await fetch("https://api.webcrawlerapi.com/v1/scrape", {

method: "POST",

headers: {

Authorization: "Bearer YOUR_API_KEY",

"Content-Type": "application/json",

},

body: JSON.stringify({

url: "https://example.com/article",

main_content_only: true,

scrape_type: "markdown",

}),

});

If you want to see the code-first tutorial, here is my practical guide: Extracting article or blogpost content with Mozilla Readability.